Sure, but don’t sweat the small stuff.

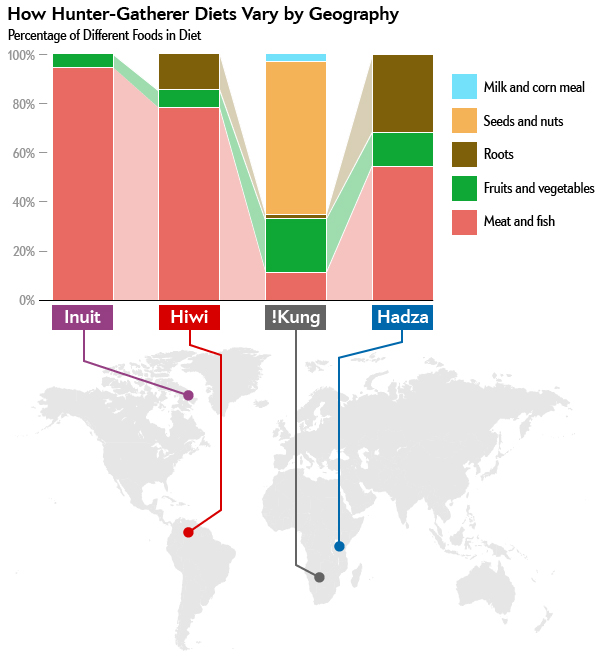

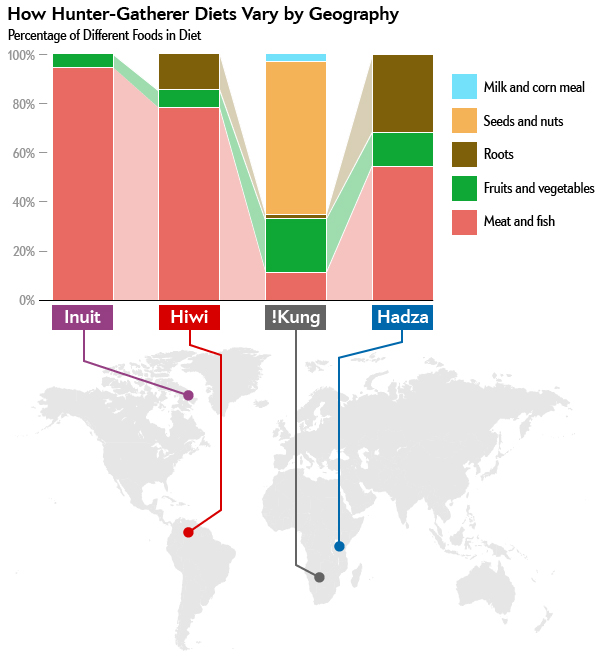

The Paleo diet is, in its strict form, a narrow selection of foods, specifically sourced, meant to approximate our ancestral diets. The Paleo claim is that we have not evolved quickly enough to adapt to our current food environment, so we must eat more “primally,” as we are adapted to do. The claim is oversold – we have, in fact, adapted quite a bit with our changing diets; our ancestors in the period at issue ate a wide variety of foods, whatever was available where they were, basically (both a reflection of and a continued stimulus for our adaptability); and selective breeding of food animals and plants means that the foods available to us are even less like their Paleolithic ancestors than we are like ours.

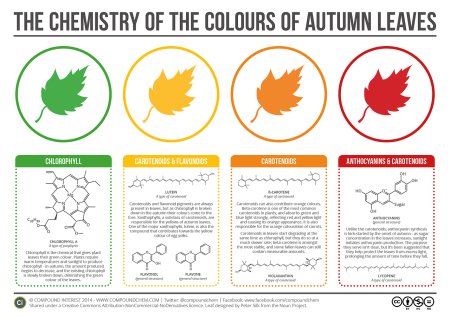

From How to Really Eat Like a Hunter-Gatherer

But that doesn’t mean you should avoid the Paleo food pattern altogether. Remember Michael Pollan’s advice, “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants”? It’s kinda like that, only more meat. The general blueprint of Paleo is a fine one: lots of high-density protein, lots of fiber-rich whole foods, and knock back on the refined/processed foods. Really nothing to argue with there. (Strict Paleo goes a lot further – no grains at all, no legumes, limited fruit, no dairy, and no sugar sweeteners, although a little honey is OK. It also encompasses recommendations for how the food is grown or raised.) Probably the worst thing about it is that its meat-heaviness and prominence of some unusual ingredients makes it kind of expensive.

If you already have lactose intolerance or feel crummy when you eat wheat, Paleo can help you organize your options, but if you don’t, those restrictions don’t have much to offer. Similarly, if you’re the kind of person who finds it hard to set limits when there’s a cake in front of you, a Paleo focus, similar to Atkins or any other high-protein/limited-carb approach, can help you build a food pattern that keeps you out of harm’s way. For most people, the most restrictive details of Paleo can be treated as mere suggestions (from a health perspective), and there are now dozens of websites discussing food options and offering inventive recipes, so Paleo can give you good ideas for how to keep home-cooked food interesting, and explore the many options outside the (processed) food industry’s heavily marketed product range.

You’ll have to say goodbye to all this, though, to follow the Paleo food pattern strictly. —Photo: Caitlin Burke

What about fat?

The Paleo food pattern is pretty fatty, and fellow-traveling approaches to idealized diets claim that our primal food pattern had as much as 75% of calories from fat. (It’s doubtful humans routinely had access to that volume of fat, though.) The short version is that if you don’t already have major health issues, like heart disease or a family history of it, and especially if you exercise regularly (every other day to daily), the kind of fat present in the Paleo diet probably doesn’t matter. After all, deep-fried food is not Paleo!

In with eggs – a free-feed food for Paleo eaters! My stepfather raised the turkeys and chickens that produced these. —Photo: Caitlin Burke

The longer answer is that the same rule of thumb probably applies to most of us, too. Fat got a bad rap in the 1950s with high-profile results from studies of heart disease and the fact that it has a lot of calories, gram for gram, making it a juicy target for calorie restriction. The problem is context. In healthy people with no major risks for heart disease, especially if they’re active, fat intake is probably not that important as a risk factor by itself. And that doesn’t even get into the different adaptations of people on different foods patterns around the world (including variations in the bacteria in our guts that help us digest food). Anything can be a problem if you overdo it, but let’s take “healthy” and “active” to mean people getting regular exercise and eating a balance (not surplus) of calories overall.

One problem with “low fat” as an approach, especially as used by the food industry, is that it often goes hand in hand with “more sugar.” This is a one-two punch, because the lower-calorie benefit of the reduced fat can be undermined by the health risk of disproportionate sugar intake, AND fat acts as a “satiety signal,” helping you to feel full, so it may be harder to exercise portion control with lower levels of it. Consider the packaging for Red Vines: Always fat free! Right, because they are basically 100% sugar. Look, I love Red Vines way more than the average bear, but we all know how hard it is to stop eating ’em. (Serious question: Why on earth are candy labels allowed to tout “fat-free food” on the front of the packaging as if it’s a health claim? George Orwell would gasp.)

Many hyped diet plans treat sugar and other carbs like poison, but a bigger problem for our waistlines has been the way the food-processing industry has stripped the fiber out of our foods. Paleo carbs come mainly from whole vegetables, a good source of dietary fiber. —Photo: Caitlin Burke

Exercise

Exercise almost never gets mentioned enough with any hyped food pattern – some even claim you “don’t need exercise” with their plan (and I know I’ve heard that claim plenty from people on low-carb, high-protein patterns). Loren Cordain, a major, active proponent of Paleo, pushes the point that the ancestors in question probably exercised about three times as much as current US guidelines for recommended levels of exercise.

An hour a day of exercise is not as scary as it might sound – it’s not like our ancestors were killing it in powerlifting-specialized gyms or constantly training for the Paleolympics. A lot of their activity was low intensity – like walking. And if you now exercise much less than that, don’t rush it; ramp up slowly, because it’s safer, and because if you are sedentary now, every little bit helps, so you will still start to benefit right away. No matter what food pattern you choose, ultimately you should aim for average of an hour or so of activity a day (again: low-intensity activity counts), and can benefit from doing something every day. If you exercise daily because you really love to work out, make sure some days are just low-key stuff, to prevent overuse injury.

In Short

Pros: The small-p “paleo” approach is a good framework for shifting a food pattern from less healthy to more healthy. With its emphasis on nutrient-dense, satisfying foods – and its rejection of processed foods – people often find that eating this way makes it easier for them to eat more nutritiously while controlling their calorie intake. The general idea of paleo – plenty of protein, lots of vegetables, minimal processed food – is appropriate for everyone who doesn’t have a protein-metabolism disorder, you know, pretty much everyone. Also, people feel good on Paleo, an effect reported by people on other high-protein, carb-limited food patterns, too. Maybe it’s the energy bump from the protein, maybe it’s getting enough protein in the first place. And sometimes, as a social-site contact of mine remarked, it’s just that “people feel better eating paleo because before that, they had never eaten a meal they prepared themselves.” Whatever food pattern you choose, be sure to exercise, too.

From an older Beef Checkoff campaign.

Cons: Paleo makes a lot of claims for support that are irrelevant (for example, we can’t eat as our distant ancestors did because the foods are simply no longer available) or wrong (we are evolving – coevolving with our environments – because adaptability is how we wildly successful species do it). Fortunately, we can dispense with those claims, because we don’t need to look that far to find good support for the basic idea of eating nutrient-dense food and avoiding processed food. (If you need a good counterexample, though, it’s lactase persistence. Lactose tolerance in adults seems to have developed in no fewer than 4 different ways over recent millennia – a pretty good track record for adaptability.)

Caution: Strict paleo is expensive, the foods can be hard to source, and it can be so demanding of time and effort that some people may find it sucks joy out of eating. Fortunately, in healthy people, this approach is more of an “if it floats your boat” thing than a delicate balance that must be preserved or trouble will ensue. So if it’s making you miserable, relax your approach while keeping the principles of plenty of protein, plenty of vegetables, and limited refined/processed foods.

More:

In 1975 Walter L. Voegtlin, a gastroenterologist, published a book called The Stone-Age Diet. It offered a basic structure for the Paleo movement. (It’s now out of print, with no plans for a reprinting, but can occasionally be found in libraries.)

What to Eat on the Paleo Diet, from the site for Loren Cordain’s books. Cordain published The Paleo Diet in 2002 (updated in 2010), and has published often and widely about this approach since 1997. He also points out that we should be exercising as our ancestors did – probably about triple the level of activity recommended by current US guidelines – a great idea that somehow gets a lot less attention than the diet itself.

Some Like It Paleo, a food blog by a Crossfit athlete in San Francisco. She has a list of resources, pointing to other sites about Paleo in general and featuring recipes.

The Caveman Controversy: Marlene Zuk has made some interesting discoveries about rapid evolution in animals – and has really angered some Paleo proponents with a provocatively titled book.

Debunking the Paleo Diet, by Christina Warinner – a TEDx talk, and those can be variable in quality, but this is a wonderful one – plus, what a great truncation in the link’s name!

Ancel Keys was a major figure in dietary fat in health, who identified animal fat as a risk factor in the 1950s and promoted the Mediterranean diet. His work was a foundation for the US government’s recommendation of low-fat diets.

Culprit in Heart Disease Goes Beyond Meat’s Fat reports on an interesting study showing how complex eating is – it’s not just the saturated fat in red meat that Keys pointed to, it’s what gut bacteria we have to interact with the foods themselves. This is a small detail in a growing literature about the variety of collections of gut microbes across and within populations around the world.

Go Kaleo, by Amber Rogers, a website about breaking the dieting cycle. Lots of good info about food patterns, exercise, and putting it all together in a way that won’t make you crazy.

The 4 Most Important Things about Flexible Dieting, by Armi Legge. A list of considerations for any food pattern you are thinking about, it emphasizes long-term thinking and having a food pattern you like.

Update March 2014: Don’t Fear The Fat: Experts Question Saturated Fat Guidelines – discusses recent thoughts about the cholesterol–dietary fat–carbohydrate story.