So Oprah is on Weight Watchers. She recently bought WW stock, which then appreciated like gangbusters, so she has that going for her, which is nice.

I’m seeing a lot of posts chewing over this news, many with disappointment and general comments about the “impossibility” of losing weight. Even if you are Oprah, and rich, and capable, and surrounded by opportunities for help and support.

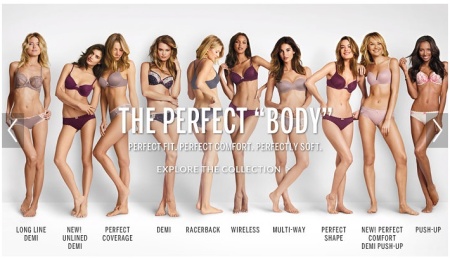

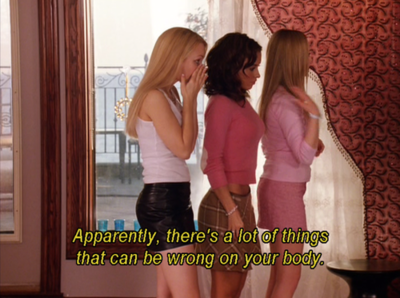

It’s not impossible to lose weight, but it’s difficult, frustrating, and draining to do things you dislike for reasons that are tied to sadness. If you are mired in a belief that “inside every overweight woman is the woman she knows she can be,” then your framing is your prison. Because if that woman is “inside” you, she IS you.

You can’t take good care of something you hate.

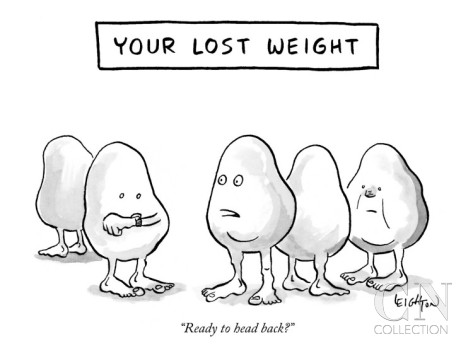

Acceptance in its various forms is often denigrated as passivity, as giving up, as the sweatpants and pint of ice cream of the soul. But sweatpants and ice cream are a perfectly enjoyable part of anyone’s life, and then you put them away, have a good night’s sleep, and get dressed for work and have an apple or whatever and life goes on. You can choose to make a habit of healthful living, and you can choose to make a habit of self-care and enjoyment, too.

Ultimately we are what we repeatedly do. If you keep punishing yourself for some notional failure, trying every 30-day fix out there in hopes something will stick, what will stick is restless program-hopping and the sense of failure. Give yourself the gift of walking away from that. Don’t try to change everything at once, but instead choose one small thing and practice it until you don’t have to think about it anymore. Then build on that track record of success.

I blogged about these issues for a year at Starter Steps. Here is a little more about how to make changes with more confidence, and how to think about which changes to focus on. Give yourself time, treat yourself the way you would like to be treated, and you can make changes that make your life better.