It’s on. I registered for Thing-a-Day again. They’re using Posterous this year, so I created a Posterous stream for it. I am hoping that this judgmental cat will help keep me on track.

Is there anything else on Posterous I should be following?

It’s on. I registered for Thing-a-Day again. They’re using Posterous this year, so I created a Posterous stream for it. I am hoping that this judgmental cat will help keep me on track.

Is there anything else on Posterous I should be following?

Does anybody remember what using a computer is like? I spent a week after reinstalling my operating system picking out the right tweaks and gizmos and gadgets to make things more manageable. Weblogs exist that do nothing but teach you how you can make your experience on a computer less shitty. On a closed system, you can’t do that. You work with what you’ve got. —Rory Marinich, “I Love Walled Gardens”

Marinich goes on to extol the virtues of having a sandbox to start in instead of having an expert system that must be learned before you can make anything. He’s absolutely right – not least because lower barriers to entry mean more people will experiment but because the more people who experiment, the broader the range of potential creations are out there, because that broadens the range of itches that people will discover and be inspired to scratch. (Besides, expert users who want to root around on the insides: isn’t that what the dev kit is for?)

He speaks harshly about the role of compulsive behavior in the environment in which people often define success in computing, but it’s impossible not to nod along with him, especially after another Apple release cycle. He is spot on about the people who speculated wildly, overexamined every leak, made elaborate laundry lists of every little thing a new Apple product should do, and then freaked out when Steve didn’t deliver exactly what they imagined. I happen to enjoy watching that particular parade unfold, but it seems like an agonizing place for the people marching in it.

And they must be getting tired after making the same complaints over and over again for so long.

One thing Sweethearts lovers can count on each year is the candy’s simple formula. Since the hearts inception, the recipe has remained basically unchanged. —NECCO® Sweethearts page

For decades one of my very favorite things has been the chalky confection known as the conversation heart. NECCO makes the good ones; I have no interest in the Brach version.

Until this year. I went to the local drugstore, and the packaging was utterly wrong – all opaque, no view of the candy. And it smelled wrong. Not, like, up close, but from a distance. Like Sweethearts Tarts. I looked for citric acid in the ingredient list, and no dice. I bought a small box for experimental purposes. Gross. Not just the wrong taste, but bumped flavors for the different colors, like someone overdoing the saturation on a photograph and ending up with colors that are just plain odd.

They issued an egg style of the candy for Easter a couple years ago, and they were absolutely foul. These are not as foul as those were, but they are NOT the traditional NECCO Sweethearts. And I don’t have the heart to try Brach’s this year and see if those are an acceptable port in this storm.

Valentine’s Day is cancelled.

Update, Feb 2014: My local grocery sold these during Valentine season as bulk candy. I also found an almost identical formula in individual boxes branded BRACH, but the BRACH-branded bags were different. It makes me crazy these are still manufactured but so arbitrarily marketed. I can’t be the only person who bonded so hard to these in childhood!

Daniel Golden, former WSJ writer: One of the tragedies of the sale of the Journal is that it never aroused the public outrage that the sale of the New York Times would have, right? I think people looked at it and said, “Big deal. A right-wing tycoon is buying a right-wing newspaper.” But the reality was that for those of us in the news operation it didn’t feel like a right-wing newspaper. It felt like a great, independent, muckraking, thoughtful news and analysis operation that played an indispensable role in American society. People who weren’t familiar with the paper didn’t realize it was an awful lot more than an editorial page.

At the end of last year, family members, staff, ex-staff, and several anonymice remarked on the sale of The Wall Street Journal to Rupert Murdoch. Daniel Golden in particular says a lot of what I was thinking as I watched the sale and have watched the paper change—particularly becoming more diffuse and less interesting in its coverage. Also, I can’t quite believe I just linked to GQ.

Wilson A Bentley photographed 5,000 snowflakes in his lifetime, beginning at age 19, recording thousands of patterns that would otherwise be lost to temperature and time.

See the gallery at the Guardian site.

The halls and rooms on the upper floors are for hobbies. Here people make pottery, draw and paint pictures, build model airplanes, or play musical instruments. There are teachers to help you with every hobby.

A very popular room is the library. There are no books. The floor is shaped into tables and benches. Built into these tables are hundreds of vision phones. The books, films, and newspapers are all stored in the library computer.

First you dial the library index. This file contains all the books that have ever been written. It does not matter whether they were first written in Chinese or French. They will be here, translated into English. There is also an index of films and newspapers. You could spend all day watching comics, but it wouldn’t be a good idea.

This is a single page from a children’s book about how the future would look.

Back when I was a boy, I bought a children’s book at my town’s library book sale called “2010: Living in the Future” by Geoffrey Hoyle. Written in 1972, it had been withdrawn from the library’s collection by the mid-80s, when I picked it up. I’ve somehow managed to hang onto it for 25 years and now, suddenly, here we are: 2010. I’m reproducing this long out-of-print book here to see how we’re doing. Are we really living in the future? | a project by Daniel Sinker

Read the whole thing at Sinker’s project site. (Bonus, Geoffrey Hoyle is the son of legendary astronomer Fred Hoyle, coiner of the term Big Bang. Learn more about the father at this site dedicated to his life and work.)

Tonight I heard Atul Gawande speak about the issues in his new book, The Checklist Manifesto. He led with a case report of a 3-year-old girl who fell into a frigid lake in Austria and was not only revived, after many patient interventions at a local hospital, but was restored to normal function over a period of regular therapy. He then discussed the development and hitches of the WHO project to develop a checklist for surgical procedures that could consistently improve the safety of surgical procedures.

Gawande is an engaging speaker, with a calm and quiet demeanor that must be immensely reassuring to his patients. I have met a lot of surgeons, and they aren’t always as nice to their coworkers as they are outside the hospital, but he clearly gets it: checklists don’t just enhance safety and improve outcomes, they also provide support for any team member to say, hey, wait a minute, is this right? Gawande reports thinking, even as he embarked on this project, that he didn’t need to use checklists himself. After all, these lists were intended to improve care in developing nations; he was at Harvard. But he used them anyway, and they improved outcomes. He seems to embrace the way they democratize the team, too, fully understanding the significance of one the items that got the most resistance: that everyone introduce himself by name. And that most team members in the operating room used first names, but surgeons don’t.

As a person who’s done some rock climbing and who has flown in a friend’s single-engine plane, I don’t find the idea that a checklist is important to be new – and this applies not “even” but especially to experts, who are somewhat prone to presumption. It’s almost a little absurd to think of an individual assuming that he personally (and in surgery, more than two-thirds of the time, it’s a he) knows so much about everything that can happen in the operating room that he can afford to be dictatorial, and not even know his team member’s names. This seems obvious in medicine, which has changed so much during the careers of still-practicing surgeons. But it is illuminating to learn that airplane pilots had to come around to checklists, too, beginning as surgeons have with highly heirarchical teams that they directed with little opportunity for questions.

A couple of European countries have reported full adoption of the WHO-sponsored surgical checklist, but Gawande told us that in the United States, uptake is around 1 hospital in 5. It is wrong to suggest that doctors don’t understand as well as airline pilots that lives can be lost if they make a mistake, and yet it’s not enough to note that it’s expected in medicine that some lives will in fact be lost, and that’s nobody’s fault. I was struck by one particularly big difference: a pilot or a climber is also at risk of death if they make a mistake or miss something – a risk most surgeons don’t face in the operating room. I hope that’s not what it takes to make American surgeons use checklists.

“Mother and Child”

The stained glass dog art version of the famous photo taken in 1966 for LIFE Magazine of a puppy Basset Hound pulling the ear of it’s Mother. Signed by the artist Holly Klay, this Basset Hound art utilizes light opaque glass for both dogs and clear textured glass with swirls for the background.

This is a large Basset Hound art piece, measuring 20″ X 13″, and is beautifully framed using lightweight zinc with a chain that can be adjusted according to your hanging needs.

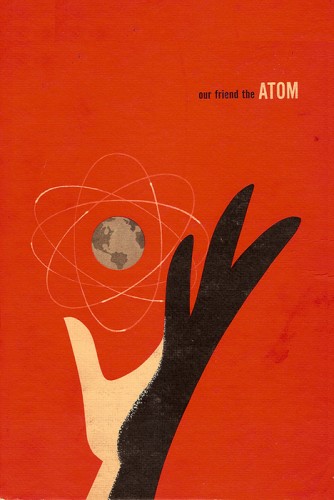

This is the cover of a Disney book from the mid 50s (56-57), companion to a short film. I haven’t seen it myself, but I’d like to. Matt Springer describes it:

It’s one of the things that made me so interested in physics. Well, actually I suppose the cover looks more Russian Constructivist, but I’m no art critic. The interior contains a solidly Art Deco inspired Futurist aesthetic. That’s what today was supposed to look like back then. The science in the book is quite solid as well. In fact, I’d like to scan some of the pages and write a series of posts on it. It really did manage to inspire a sense of wonderment, which is pretty amazing for a book about the history and applications of atomic physics. Will we ever see that kind of optimistic vision of science again?