Yesterday on my bike ride, I saw another person in a park gazing awe-struck at a raptor. This is the third time in a couple of weeks I’ve seen this. I’m in favor of anything that causes someone to stop and recognize the immediacy of nature, red in tooth and claw, but they seem to gaze with a reverence that is usually reserved for rarity. Raptors are not rare in San Francisco – several kinds of hawks are very successful throughout North America, except in the high arctic and in unbroken forest, and the Bay area is both a good place for raptors and right on a major migration route.

The red-tailed hawk, which is sighted thousands of times a year according to the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, is considered a “least concern species.” In some ways, human development has benefited these and other hawks, by giving them poles to perch on and a mix of cleared and standing trees to provide hunting grounds and nesting areas. The Cooper’s hawk and the sharp-shinned hawk are the other most commonly sighted hawks here, thriving as they do with access to a mix of clear and wooded areas. The sharp-shinned hawk sticks to denser tree cover than some of the others, in part because this smaller hawk is sometimes preyed on by Cooper’s and other larger raptors. Ospreys – though not a common sight in San Francisco – are regularly present and also considered a least-concern species, in spite of some having been threatened by widespread use of insecticides such as DDT in the middle of the last century.

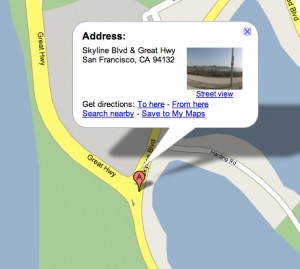

Around Lake Merced and in Golden Gate Park, raptors often keep an eye out for little rodents and other small mammals on the ground. Yesterday’s bird – a red-tailed hawk – was sitting on top of a streetlight, scanning around the road toward the golf course beside Lake Merced (perhaps thinking that if that runner kept staring, frozen, it would eat like a king that night). I’ve seen hawks successfully grab a meal in the park, too – once, memorably, mere feet away from a toddler that was excitedly babbling to his mother about the gopher that had just peeked out of its hole.

The Golden Gate Raptor Observatory conducts counting and banding activities every fall, educates the public about its activities, and reports its findings about raptor populations flying in the Bay area. Donors receive an annual newsletter and season sightings summary.