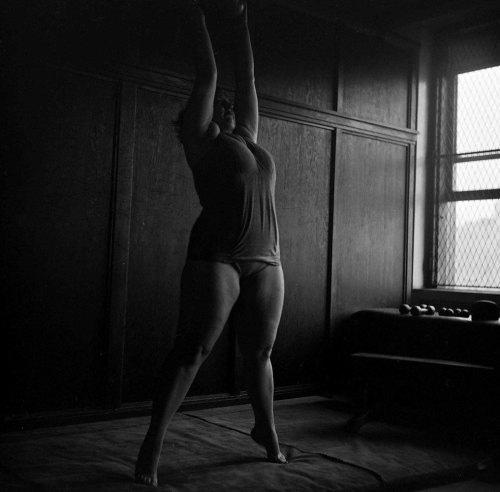

Photo by Martha Holmes — Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Dorothy Bradley, photographed for LIFE magazine article on obesity, works out in 1949.

—From Obesity: Photos From the Early Fight Against a Health Crisis, 1954

LIFE recently published a series of photos taken during the reporting of a story it published in 1954, about the problem of obesity. It features Dorothy Bradley, who embarked on a program of losing more than 50 pounds using a combination of changes in eating habits and getting more exercise. The photos show her in the gym in sweats, in a swimsuit preparing to swim, trying on dresses, sitting at a diner counter, wedging herself through a turnstile. And finally on a dance floor in a ballgown showing off her newly pared-down waist.

I love this photo in particular. We can clearly see a strong body, and an essentially aesthetic silhouette. Dorothy probably had many advantages over people who embark on this journey today at the same starting weight she did: she probably had more activity built into her day getting to and from work, and fewer labor-saving devices at work and at home. Although she may have eaten carbohydrate- and fat-heavy foods, they were less processed than typical foods in today’s environment. Another photo shows her with a slim, grim-faced nutritionist, behind whom is a poster listing “MUST FOODS – EAT DAILY” (milk, meat/fish, citrus, other fruit, vegetables, grains, fats – one wonders if they were meant to be eaten in that order). We learn that she was pursuing nursing (and did so successfully). Yet, with all these environmental advantages, and her explicit interest in health and healthcare, she had to lose the majority of this weight twice before she kept it off.

LIFE meant to show that the obesity epidemic is not new, but I think these photos show us something important about how unhelpful our messages about weight and health have become. The buried lede is exercise. One of the captions reads, “In gym in New York sweat-suited Dorothy finds workout did not by itself remove pounds but did help avoid flabbiness as she lost weight dieting.” Fitness experts love to tell people that “exercise doesn’t work,” but that caption and the photo above tell a different story. It may well be that “abs are made in the kitchen,” but nobody needs visible, ripped abs. People need stable blood sugar, a good blood lipid profile, a good red blood cell count, enough body fat to support cell functions and aid in recovery but not so much that organs lose function by being packed in it. And those goals are better supported by regular, low- and moderate-intensity exercise than by a specific diet – and the exercise can stabilize mood and lift the energy level as well.

One notable thing about these photos is Bradley’s relative isolation. We certainly don’t see any shouting trainers. We see Bradley wrestling with her body image out in the world, but mainly we see her alone with her exercise and tape measure. I find these to be surprisingly positive images. This is doable. It helps to have some consultation, which we see with the nutritionist, and it helps to know why you’re doing this, which we see with others around her, but ultimately the work itself is you alone – it’s you with your food choices and with your exercise. And the path may not be strictly linear, but you can make it if you take the long view.

Among the least-helpful cultural baggage surrounding obesity is persistent messaging that focuses on looks. Obesity is a look onto which people feel free to project assumptions of laziness, incompetence, ignorance. We still have a way to go in understanding how body fat, conditioning, and nutrition combine to support healthy outcomes, but research results are trickling in, suggesting that you definitely can be too thin (although for good health outcomes in the US, it still helps to be rich). High-protein eaters with heavy exercise schedules are helping to challenge claims about saturated fat dating back to the 1950s, and gut flora libraries are being assembled and coordinated with food records to add more pieces to the food-and-health puzzle. I hope that this better information environment can help us pay more attention to what we’re really trying to affect when we talk about addressing the obesity epidemic: bad health outcomes, early mortality, lost productivity, rising healthcare costs. And although we still need cheap, simple methods for tracking, like weight scales and tape measures, here’s hoping we can see them for what they are – approximate tools instead of final arbiters.