A Facebook friend of mine liked a post from Dana Linn Bailey tonight. Bailey is a bodybuilder, and she posted a full-length photo of herself in the gym. As always when a woman shares a photograph of herself, the post attracted lots of comments passing judgment on her appearance. Bailey has lots of loving fans, but the Internet really seems to encourage the kind of guy who has to tell the world that some arbitrary woman does not appeal to him, as if it matters. And some of those men favored Bailey with comments along the lines of her looking like a man.

This is a hot-button issue wherever women touch weights. There persists a Victorian fantasy of women as fragile creatures, perpetuated by increasingly confused claims about what’s ladylike, and idiot celebrity trainers who insist no woman should lift weights heavier than 3 lb. Never mind that a gallon of milk is over 8 lb, potatoes comes in 10-lb sacks, and children – and handbags – often weigh much more, and no one seems to think women should be exempt from handling them. If a woman has the temerity to do exactly the kind of conditioning that will enable her to handle all those womanly duties with greater efficiency, a better energy level, and less risk of injury – watch out! Who knows what horrors might lie around the corner!

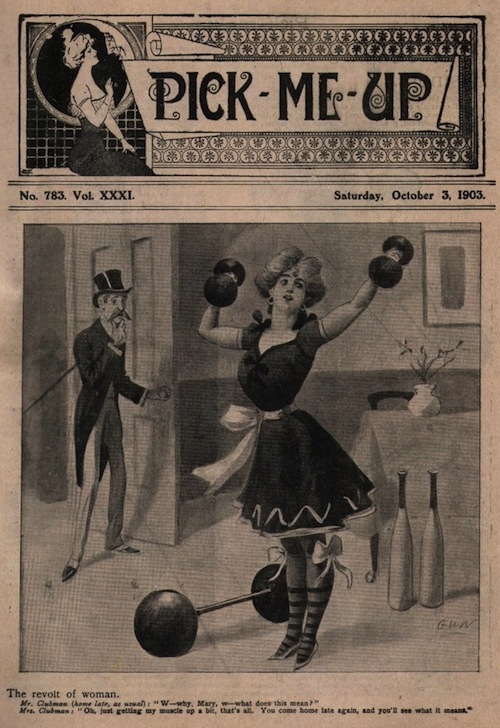

Cartoons about women exercising, and similar cartoons about woman suffrage, played on the assumption that the mere possibility of women narrowing the gap between what men and women could do would necessarily lead to abusive behavior. Pretty interesting statement about what being “manly” really means. (Larger)

If a woman lifts weights or develops her body for personal reasons, she’s especially threatening. I’m sympathetic to this point of view. I remember how much more competent and independent I felt after I started doing some lifting. And those feelings can lead to confidence, and to abandoning wide-eyed gratitude for offers of help – possibly even not hearing them, because you are too busy just going ahead and lifting that box or carrying that whatever-it-is.

It’s tempting to ascribe the negative responses to women’s strength as simple misogyny tinged with a fear that strong women can treat men the way men have been treating women. But there’s a kinder, gentler fear in there somewhere, too: in a society in which we’ve defined women as needing the help of men, what happens when they don’t need that help anymore? Will they not need men? Both of those fears are as hostile to men – painting them as essentially brutal or basically worthless – as they are to women. We all deserve better than that.

In the fitness world, some people spend a lot of time dismissing women’s concerns about looking like men because they lift, and I’d love to see this stop for two reasons:

- It’s a moving target. You don’t know what a woman is thinking of when she expresses that worry, and women do get told they are mannish, almost no matter what they look like. I suspect much of it has to do with confidence and independence – that a woman just having a can-do attitude, and dropping the slack-jawed, tentative stuff, rubs a lot of people the wrong way. So you can never reliably promise a woman that she “won’t look mannish” – the genuine concern (and negative attention she gets) might not even be about looks in the first place.

- Who cares if they do? Seriously, who cares about this? Women may seek a particular look, and I’m all for that, whatever it is, as long as they don’t feel ashamed or coerced into seeking it – and that goes triple for “feminine” looks. And then there’s women like Dana Linn Bailey. She knows what she’s doing! She’s built a successful professional life with that look, carefully and deliberately. If you act like there is something wrong with that, it is entirely on you – it has less than nothing to do with her.

We don’t need to worry about women looking mannish (or men looking womanly). We need to worry about why we think it’s a problem if they do. Men and women have a lot of differences, and sometimes it does seem like we are from different planets, but we’re not. We’re both from Earth, and we are both part of the same species. We are more alike than we are different, and the idea that one of us resembling the other can be taken as an insult is an absurdity that has meaning only if you think that one of those things is necessarily inferior.