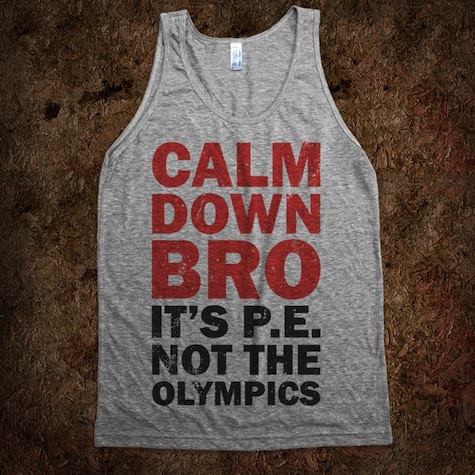

This is pretty good advice. Mostly.

We all need a little perspective, and athletics really seems to bring out the lack of perspective in people. Usually it’s something more like Larry Bird’s “Push yourself again and again. Don’t give an inch until the final buzzer sounds,” although that quote’s unusual for its use of context: while the competition is on, you need to be, too, but there’s also an end, a time to stop pushing. For the buyers of this t-shirt, apparently the time to let it slide is whenever you’re not actually competing in a world-stage event.

Treating PE like the Olympics is almost certainly the hallmark of people who are going to make it there, though. I learn pretty easily, so it was clear to me early on that the difference between being good at something and being great at something was craft, practice, and that means drive. The greater your drive, the more you work, even when you’re already terrific, because the thing itself is the thing. We see this in many areas that cause people to ask “is it talent or practice?” It’s both. You need to do it, to inhabit it, to know every aspect of it. PE is one of thousands of dress rehearsals that will make that Olympic performance shine.

As with many things, the problem here is not a behavior but a response to that behavior. This t-shirt, whose message amounts to, “hey, crab, get back in the bucket,” has some problems bound up with its self-evident truth. But I don’t think the feeling it reflects is truly a reaction to that ultra-competitive kid. I think it’s about the PE teachers and coaches and parents who lionize aggressive, sometimes reckless competitive drive as if it is inherently valuable, thereby chiding – sometimes directly – kids who don’t have it.

I believe life is better – richer and more satisfying – when you have something that makes you feel like you’re striving for a world-class performance. Even if you never hit a truly competitive level, the IKEA effect endows your own efforts with value above the objective reality of the result. Some people will never discover anything that makes them feel that way, and some people only feel pressured by it – that’s fine, too. There’s almost 7 billion ways to live. So if you’re around kids a lot, it’s good to find ways to praise strong drive and high performance that doesn’t also trash the kids who may not have found their bliss yet, or who may prefer a less intense existence. Plus, the IKEA effect dissipates when people fail to complete a task, so don’t go actively discouraging kids who are in the midst of working on something – your downer attitude might follow them around.

People who encourage intensely competitive behavior in kids like to point out that there’s only one winner, that second place is “first loser.” I suspect the kids who are destined for the Olympics don’t really need the stick, so it’s needlessly insulting language to the kids who can plainly see this isn’t their domain, which may well sap their interest in finding a way to be engaged and excited at a different level or in a similar specialty. It privileges a few narrows ways to be successful, and it places too much emphasis on success as something one does alone. Our world is big and complex, and all the most interesting things – going to the moon, reducing the toll of childhood-preventable disease, building almost anything at a larger-than-personal scale – require groups of people, bringing different strengths and working together.

Individual achievement is inherently satisfying, an important reinforcement for continuing to put in the work that supports it. It also provides a foundation for group success, by developing the abilities that individuals will bring to group efforts in order to collaborate effectively for the majority of their lives. People are more likely to discover and develop those strengths in an environment that says “everyone is good at something – let’s find your thing” than one that just gives a few options, celebrates the #1s, and browbeats the “losers.” That all-or-nothing approach doesn’t just mislead kids on their way to learning to live in the real world, it also deprives them of a simple pleasure in community – and an important life skill: being able to share the excitement of that ultra-competitive classmate and say, “You GO! You make PE into the Olympics!”