It’s been celebrated in a Google doodle, and has triggered articles on everything from how fantastic women are to “why is this still a problem when we supposedly know how fantastic women are?” It’s been observed for over 100 years, with roots in the workers movements of the early 20th century.

This year, International Women’s Day arrives as I’ve been reading about the development of physical culture in the US, particularly how women were addressed and presented. A friend recommended the wonderful Venus with Biceps, a book discussed at length by Maria Popova at Brain Pickings.

The Braselly Sisters, above, were a pair of strongwomen who specialized in graceful and artistic strength stunts. They were sisters of the even more famous Katie Sandwina. But physical culture and athletics for women were shaped by far more than circus acts.

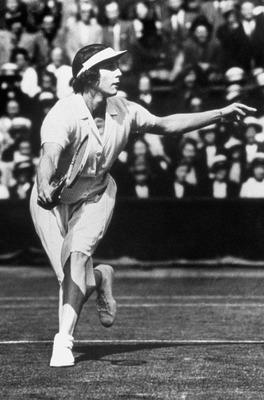

Helen Wills (1905-1998) achieved international fame as an athlete with a phenomenal string of tennis victories, including 2 Olympic golds, 7 US Open grand slams, and a career streak of 158 wins.

An excellent student, dedicated athlete, and active writer and painter, Wills was described by others as reticent, shy, and awkward. She had a style of play described by competitor Helen Jacobs as “a machine… with implacable concentration and undeniable skill” but (and?) by Charlie Chaplin as the most beautiful thing he had ever seen. Her introverted and detached style cost her popularity during her career, and can hardly help but fascinate in a society that is grappling with what it means to be neurotypical. In her own words, “I had one thought and that was to put the ball across the net. I was simply myself, too deeply concentrated on the game for any extraneous thought.”

Kathrine Switzer made athletic history the year I was born, when she ran in the Boston Marathon. Other women had joined the race, but Switzer registered (as KV Switzer) and ran with a bib. What happened next is a startling demonstration of terrible sportsmanship.

Race official Jock Semple attacked Switzer on the course:

A big man, a huge man, with bared teeth was set to pounce, and before I could react he grabbed my shoulder and flung me back, screaming, “Get the hell out of my race and give me those numbers!” Then he swiped down my front, trying to rip off my bib number, just as I leapt backward from him.

Her boyfriend intervened (knocking Semple to the ground), and she completed the race, in an era when women were still being told they could damage their reproductive organs by running. I think the thing that disappoints me most about this incident is how appallingly recent it is.

Women running are commonplace now, all over parks and treadmills, occasionally mocked by some in the fitness industry for dogged devotion to high mileage and charity events. Almost every Olympic event now includes women, not just in track and field but into wrestling and boxing and beyond. Women still get told some pretty crazy things about one of the simplest and most basic athletic endeavors, though: weightlifting.

In Venus with Biceps, writer David Chapman notes that even when women were recommended to take up resistance training with free weights, they were started with light, wooden dumbbells – in spite of the fact that at home they were lifting laundry baskets and children that weighed much more. More than a century later, women are still getting the same messages, and hearing scare stories on par with the claim that running makes your uterus fall out. Weightlifting seems to elicit the purest fear about women: that they will “become” men.

Who could ask for a more concise counteragument than the fantastic Abbye “Pudgy” Stockton?

Stockton, who had been heavy as a teenager, took up weight training because her boyfriend brought her some equipment, and she joined him in the heyday of Muscle Beach, where they performed elegant and remarkable acrobatic and gymnastic feats together. A columnist for Strength & Health magazine, Stockton was also a popular media subject, appearing in pictorials and on covers of dozens of magazines, featured alone and with other bodybuilders. She helped to organize the first sanctioned weightlifting competitions for women, and was inducted into the International Federation of BodyBuilding & Fitness Hall of Fame.

If I have just one wish for us as women, it’s to be treated with respect as we pursue what appeals to us most. Humans are social animals, and everyone gets prescriptive messages about some things, but women bear a greater – and more patronizing – burden in this regard. Maybe on a future International Women’s Day, we could enjoy 24 hours during which the presentation of a photograph of a woman actually doing something – like powerlifting or answering questions put to her as Secretary of State – was not immediately greeted by a man judging her sex appeal (probably negatively). A girl can dream.